Eternity and a day

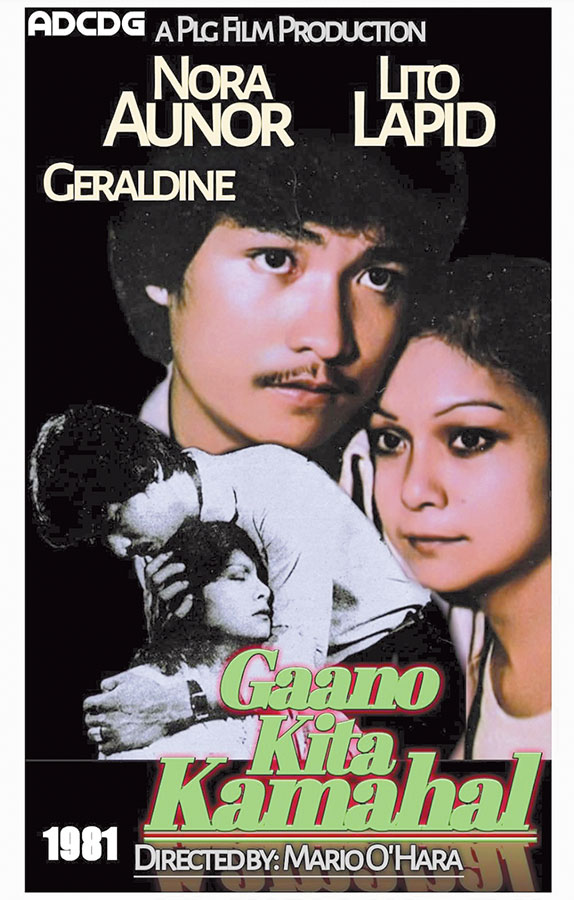

Movie Review Gaano Kita Kamahal Directed by Mario O’Hara COMING OFF the commercial and critical success of Kastilyong Buhangin (Castle of Sand, 1980), Nora Aunor, Lito Lapid, and Mario O’Hara put their heads together once more to present Gaano Kita Kamahal (How Much I Love You, 1981), a more ambitious, more lavish production. Mely Tagasa […]

Movie Review

Gaano Kita Kamahal

Directed by Mario O’Hara

COMING OFF the commercial and critical success of Kastilyong Buhangin (Castle of Sand, 1980), Nora Aunor, Lito Lapid, and Mario O’Hara put their heads together once more to present Gaano Kita Kamahal (How Much I Love You, 1981), a more ambitious, more lavish production.

COMING OFF the commercial and critical success of Kastilyong Buhangin (Castle of Sand, 1980), Nora Aunor, Lito Lapid, and Mario O’Hara put their heads together once more to present Gaano Kita Kamahal (How Much I Love You, 1981), a more ambitious, more lavish production.

Mely Tagasa and Mario O’Hara’s script for Kastilyong Buhangin told their story in fairy-tale terms — Nora and Lito’s Laura and Oscar growing up as childhood playmates, Laura tormented by her ogre foster-father, brave Oscar defending her and paying a heavy price. The die was cast long before they knew anything: Oscar was Laura’s friend — brother, almost — before falling in love; Oscar grew up not under his mother’s care but in the prison system — when released he walks about with a convict’s mentality (strike back when struck; stick to your friends no matter what; fight hard, play rough, die young). Laura, blessed by Oscar’s sacrifice, knew better — she had the talent and drive to succeed in a singing career. They were fated to follow their respective trajectories, she an uninterrupted ascent, him a downward spiral.

In Gaano Kita Kamahal (script by Daniel Martin, Greg Tadeo, Jerry O’Hara, Mario O’Hara) the tone is set by the film’s opening image, of a man in ballerina drag dancing a clumsy pas de duh while Melissa Manchester croons “Through the Eyes of Love” on the soundtrack — the dissonance between romantic ballad and graceless slapstick at once funny, ugly, and somehow poignant. We meet the lovers as strong independent-minded adults pursuing separate if parallel careers: Lito as sword master Hector, Nora as songstress Pilar. Presumably they met in a show and fell in love; presumably Hector with his strong, rugged physique felt the need to expend surplus energy not just on Pilar but on any statuesque beauty who happens to walk past — in this case singer Lucy Alba (Geraldine), daughter of veteran director Bernardo Alba (Mario Escudero), who happens to be Hector’s mentor. When Lucy gets pregnant, Hector is stuck.

Obvious why Kastilyong was such a box office smash — nothing hits harder than a pair of star-crossed lovers (ask Shakespeare), especially when you’ve followed them from childhood. Asked to repeat Kastilyong’s winning recipe O’Hara fiddles with the formula, and the result is more complicated with a hidden agenda — to pay tribute to Filipino vaudeville.

You see that agenda everywhere: the ballads, the dance numbers, the comedy skits. Señor Alba has big plans for Hector to star in his latest film production (vaudeville is dying, has been dying for years, and the jackpot is an offer to make a movie of what you’ve been performing all this time onstage). Alba playfully challenges Hector to a duel wherein the former easily disarms the latter, the director reminding Hector that he taught him everything he knows. When Hector defies Lucy’s demands to marry her, he should have known better — or does when Señor Alba sets the record straight (I can make or break you). The result is grotesque comedy with O’Hara planting the camera before the chapel altar, turning it into an impromptu stage where priest blesses the couple’s union, well-wishers shake hands, and the camera, once in a while, freezes on Hector’s face to show what he thinks of the farce.

Offered a bit of sugar and you can take or leave it depending on how you feel at the moment; prohibited from ever having sugar for the rest of your life and you develop a craving, as if to crystal meth — now Hector can’t stay away from Pilar, who doesn’t for a moment encourage him but can’t help being responsive. Early on O’Hara showed us the lovers’ normal interaction (long takes of the two bickering); once the rampart of matrimony rises between them the interactions suddenly become wordless, bitterly exchanged glances and gestures, and what starts out as a funny sketch darkens into a deeply felt passion play.

Nora is best known for her roles as dusky provinciana either being threatened by a tyrannical employer or abusive husband or drunken Japanese officer; not as well-known but should be are her films as reluctant adulterer, who falls into a love affair not entirely of her own volition, pulled into it by feelings she can’t express in words (but can, eloquently, with her eyes). One remembers that moment in Kastilyong Buhangin when Oscar pulls at Laura’s hand and the audience swoons; there’s a similar moment in Gaano where Hector seizes Pilar — Nora looks surprised, not just by Hector’s gesture but by her own feelings on the matter. O’Hara does capture lightning in a bottle a second time, at least in this moment, a gift if you like to Nora’s fans.

And sometimes it’s not the script, sometimes it’s the details enhancing the drama. O’Hara began with a sarcastic interpretation of “Through the Eyes of Love” (we meet a pair of not exactly graceful lovers), along the way quotes lines from Alan Jay Lerner’s “I’ve Grown Accustomed to (His) Face” (which Pilar sings with rueful affection while O’Hara inserts shots of Hector in bed with Lucy), and so on. O’Hara is operating in full-on musical mode, the numbers commenting, sometimes cynically, on the story. When we reach the eponymous song’s onscreen performance we’re primed to soar as Nora negotiates the ladder of consonants and vowels (Mag. Pa. Kai. Lan. Man!) that is the song’s key term (roughly put: forevermore).

Or not. Nora and Lito as adulterers? Lito as an unrepentant asshole? Where’s the mix of action and song numbers? And what’s this vaudeville shit? Audience and critics alike expected a Kastilyong 2 and got a more adult, more clear-eyed melodrama where both lovers do wrong and know they’re doing wrong (in Kastilyong you get the sense it’s the alcohol and anxiety of living in the world outside prison) but can’t help themselves anyway (the film recalls the startling conclusion to Mike Nichols’ The Graduate only here Dustin Hoffman can kick ass and Katherine Ross can actually act and sing). Most of the film is wall to wall song numbers with a sprinkling of action (the play-fencing between Hector and Señor Abla; an outdoor braw — shot handheld with only one cut mid-sequence — where Hector defends his father) — a dry slog for Lito Lapid fight fans until the closing minutes. The film was savaged by critics and bombed at the box office.

Which is a pity; thanks to the success of Kastilyong, O’Hara managed to put together a dream team of talents: production designer Benjie de Guzman, who conceived the massively elaborate kitschy sets evoking the age of vaudeville (the musical numbers coming across as George Cukor with a trace — just a trace — of deadpan Ken Russell); cinematographer Conrado Baltazar, who gave the film a brooding melancholic grandeur; and Efren Jarlego — of the Jarlego family of film editors — who did the understated but precise cutting.

Flaws? O’Hara inserts one too many melodramatic incidents (a jar of flung acid, an improbably timed car accident) while trying to maneuver his chess pieces to their inevitable conclusion, a confrontation between Hector and his mentor, Señor Alba.

I remember in an interview O’Hara citing Michael Curtiz’ The Adventures of Robin Hood as a formative childhood experience and I can see that wide-eyed child at work here, shooting the intricate swordplay in long takes, taking care to show the footwork (almost always a neglected aspect in action sequences) and how balance is always a swordsman’s concern. I wondered at the choreography — how did Lito Lapid manage to teach his adversary fencing, and how did the older Mario Escudero keep up? Turns out Escudero was the fencing master — he taught Fernando Poe, Jr. how to use the sword — and Lito Lapid the pupil, having an infernal time keeping up. Art imitates life, and so on.

Critics flinched at the prospect of a cheesy swordfight and Lapid fans were presumably disappointed he didn’t get to use his fists, but this is O’Hara again and without shame expressing his love for a dying art — the fight takes place on a stage littered with stage props, loose curtains, fallen light fixtures, continues backstage and up (of course) to the balcony, with a finale straight out of Hitchcock. Critics may have flinched and audiences failed to follow, but I had the time of my life, fashion trends in action and filmmaking be damned. Highly recommended.

(Thanks to Jojo De Vera for support and valuable information)