Philippine sovereign credit rating: An ‘A’ rating, how soon?

On Aug. 14, the Japanese credit rating agency R&I upgraded the Philippines Foreign Currency Issuer Rating to “A- with stable outlook,” one year after its last rating of “BBB, positive outlook.” Following a similar upgrade to “A-” by Japanese credit rating agency JRC, business media was abuzz with the expectation that similar rating upgrades are […]

On Aug. 14, the Japanese credit rating agency R&I upgraded the Philippines Foreign Currency Issuer Rating to “A- with stable outlook,” one year after its last rating of “BBB, positive outlook.” Following a similar upgrade to “A-” by Japanese credit rating agency JRC, business media was abuzz with the expectation that similar rating upgrades are forthcoming from the better-known credit rating agencies (CRA) Moody’s, Fitch, and Standard & Poor.

R&I and JRC are not as well-known as the big three CRAs. They are known to be “quicker to the draw” so to say, in sovereign ratings. The media reports relied only on the press release from R&I, as the pdf file of the full report from the website cannot be downloaded. R&I and JRC apparently do not cover banks or corporates.

R&I gave the Philippines the same rating as Thailand (A-, stable) and one notch lower than that of Malaysia (A+, stable). Surprisingly, Vietnam’s rating — BBB — was lower than the Philippines’ despite it having a fiscal surplus of 5.8% of GDP vs the Philippines’ deficit of 4.5%. On the other hand, it was upgraded faster from BB+, stable in February 2024.

THE CREDIT RATING FRAMEWORK AND PROCESS

My previous corporate life involved dealing with CRAs starting in 1994 with Standard & Poor, later with Fitch Ratings, and eventually Moody’s — a period that included the CRAs’ controversial roles in 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis triggered by the collapse of Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns. Capital Intelligence, a Cyprus-based CRA, covered Philippine banks in the 1990s and 2000s.

The experience gave me some familiarity with their methodologies, analytical framework, and the key metrics involved in arriving at their credit rating assessments. The bottom line of any credit rating is whether you can pay your debts when they fall due.

This column breaks down the key factors in a credit rating, mainly the macroeconomic indicators what constitute sustainable debt management. The key elements are the amount of debt, its composition (local vs foreign currency), its size relative to the size of the economy, its maturity structure, and market conditions.

HOW DEBT IS INCURRED

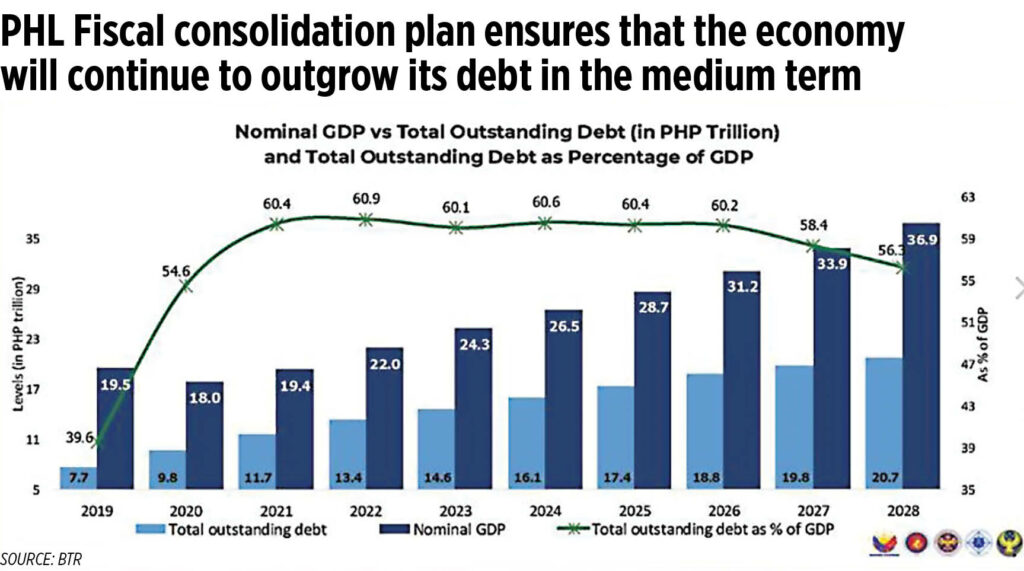

Every time the government spends more than it earns in revenues, it incurs a deficit. The gap is usually funded by borrowings. Continued fiscal deficit entails additional borrowing, adding to the stock of outstanding debt. For the period 2023-2028 under the five-year fiscal framework approved by the Development Budget Coordination Committee (DBCC), the country’s total outstanding debt is expected to grow by over P1.2 trillion a year corresponding to the amount of the fiscal deficit.

Key Point 1: Focusing the absolute amount of the outstanding debt alone is meaningless without the proper context. It is not the size of your debt, but all about the ability to pay your debt. The capacity to pay increases with a growing economy, hence declining debt to GDP means the economy is growing faster than the size of the debt, even if the absolute amount of the debt is also growing. Those who had housing loans can relate to the fact that the monthly installments are burdensome at the start but gets lighter as your income grows.

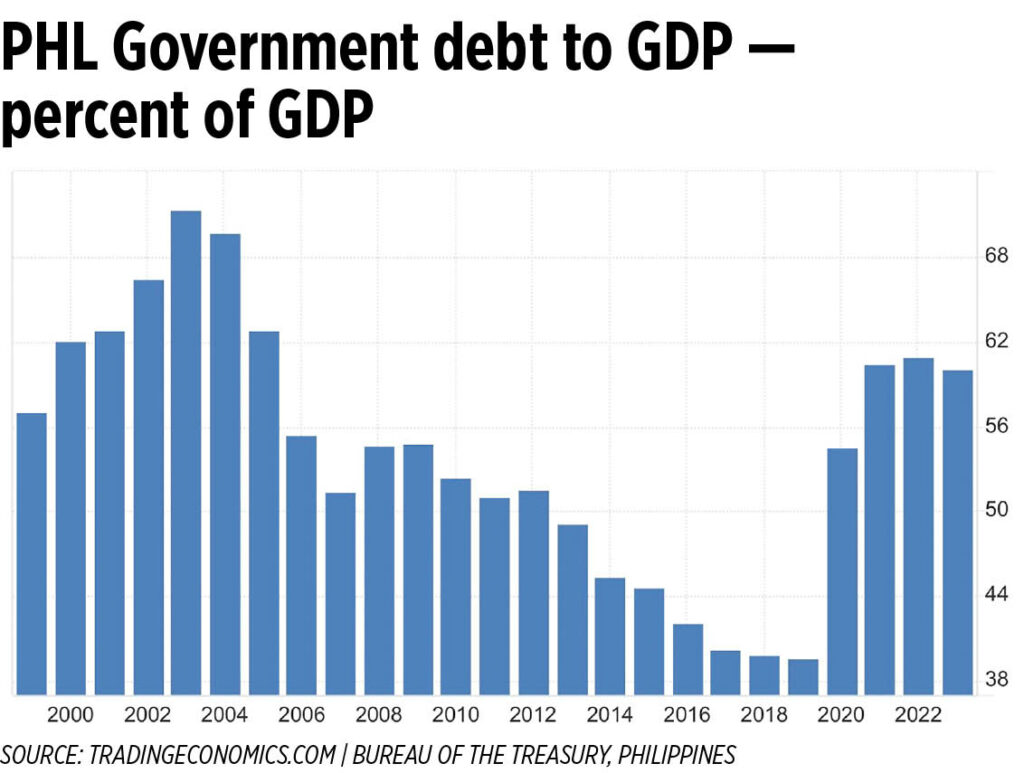

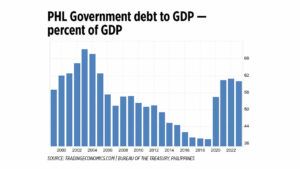

As historical context, the country’s debt to GDP ratio hit a high of 74% in 2004 when Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (GMA) was president, serving the remainder of Joseph “Erap” Estrada’s term. GMA was trailing actor Fernando Poe, Jr. or FPJ in the polls leading to the 2004 presidential elections, and she tried to gain votes by not allowing the National Power Corp. or Napocor to increase its power rates. The absorption of Napocor’s huge deficit into the consolidated public sector deficit (CPSD) pushed the fiscal deficit to 5% of GDP and the debt/GDP ratio to 74%. The resulting fiscal crisis triggered the release of a white paper from the professors of the University of the Philippines School of Economics on how to reverse the primary deficit into a surplus.

Once elected, GMA spent her political capital to support the increase in the value-added tax (VAT) from 10% to 12% (VAT Reform Act RA 9337, May 2005). The debt/GDP ratio steadily improved thereafter through the rest of her term, through President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III’s term — during which the Philippines obtained the investment grade sovereign credit rating — and during Rodrigo Duterte’s term, to a low of 39% in 2019 just before the pandemic of 2020.

THE DEBT/GDP RATIO SHOULD NOT BE CONSIDERED ALONE

Singapore’s debt to GDP ratio is 168% but it has the highest rating of AAA, because its economy is so strong and its 2023 export/GDP ratio is 174% vs. 26.7% for the Philippines. The US ratio of 129% does not matter, since the US dollar is the global reserve currency it does not have to earn the dollars (exports of goods and services) to pay its debt. It only has to print the dollars (or, technically, create a credit entry with a US Fed account).

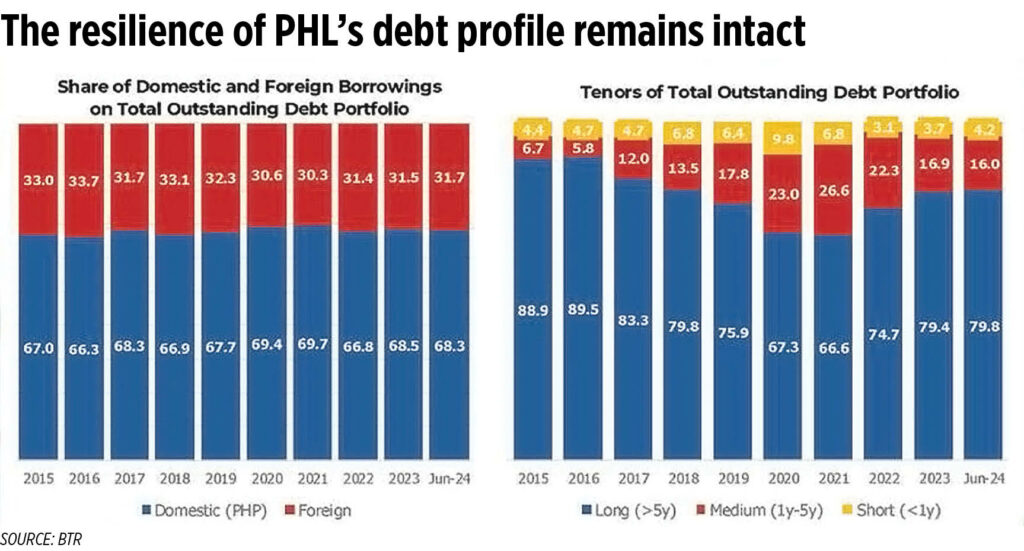

Key Point 2: The composition of the debt is important. The bulk or 80% of the debt is domestic, while only is 20% foreign — the portion of the debt subject to foreign exchange risk, or the risk that the government will not have enough dollars to pay the bonds.

The foreign exchange risk is even lower for ROP bonds, since at least half are held by local investors (mostly local banks and rich investors). The worst thing that could happen for these local holders of ROP bonds is to be paid in pesos (at current exchange rates).

Why the domestic share important: Japan’s debt to GDP ratio is 264%, but it is not considered a problem because all the debt is held by locals (43% of which is held by the Bank of Japan alone) and interest rates are very low (zero or negative) hence with practically zero cost of borrowing. This was highlighted during an extended period of negative interest rates, when banks had TO PAY the Bank of Japan to deposit instead of getting paid with interest.

Key Point 3: Maturity structure is critical. Even if your debt level is low, but the bulk of it is short term (falling due within one year), then you have a mismatch between your payments due and your cash flow. To use another consumer parallel, the amortizations for a housing loan is much lower if your maturity is 20 years vs. 10 years.

In this respect, the economic managers have managed our debt very well. The term structure management of Philippine debt has been very, very good, with 80% long term over five years, 16% medium term <1-5 years, 4% short term. The short-term ratio went up to 24% in 2020-2021 during the pandemic as sharp increase in borrowings had to make up for the fall in revenues but this has since “normalized” back to 4% of the total.

Key Point 4: International reserves as an indicator of ability to pay for imports and for foreign currency debt. Following painful lessons learned from the foreign exchange crisis in 1983-1985 (with foreign credit lines cut off, scarce foreign exchange was literally rationed every day to importers) and the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, an important part of the monetary policy stance was to make sure there are sufficient international reserves.

How much of a buffer is enough? According to its method called Assessment of Reserve Adequacy (ARA), the IMF thinks that $100 billion in reserves is more than enough. However, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Governor Eli Remolona noted that the IMF ARA methodology misses certain elements and is therefore not appropriate to the unique requirements of a developing country like the Philippines. He correctly asserted that maintaining our international reserves at the $100 billion level is the more prudent policy.

Key Point 5: A higher credit rating means a lower borrowing cost, but this is not necessarily true all the time. For example, Indonesia obtained an investment grade rating ahead of the Philippines but our ROP bonds were traded at lower interest rates than Indonesia.

The reason? The supply of ROP bonds was substantially more and the market for trading had high liquidity, coupled with competitive bids from local investors. The reduced liquidity risk of ROP bonds led to a lower rate.

The Challenge: How to maintain, even improve the Philippine sovereign credit rating to A during President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.’s term while maintaining government spending to continue to spur the economy on — especially the 5-6% infrastructure spend to GDP ratio — while reducing the debt/GDP ratio to 50% by 2028 (a fiscal deficit of at least P1.2 trillion annually). The fiscal numbers in the DBCC fiscal framework 2023-2028 appear feasible.

Recap: After the Japanese rating agencies upgraded the Philippines to A, will the Big Three follow?

On Aug. 22, Moody’s affirmed the Philippine investment grade rating of Baa2, and its outlook of “stable.” Since it did not upgrade the outlook to “positive,” it will take another year before the outlook is upgraded to “positive,” which is a necessary prior step to the upgrade of the sovereign credit rating itself.

Similarly, on Sept. 17, S&P announced in a webinar that there is no change in its BBB+ rating with a “stable” outlook.

At this rate, it will take the Big Three CRAs at least two years to upgrade the Philippines to an A rating, or by 2026 at the earliest.

Alexander C. Escucha is president of the Institute for Development and Econometric Analysis, Inc., and chairman of the UP Visayas Foundation, Inc. He is a fellow of the Foundation for Economic Freedom and a past president of the Philippine Economic Society. He wrote the Handbook on the Overview of the Banking Industry for the Banking Association of the Philippines’ 60th anniversary in 2014. He is an international resource director of The Asian Banker (Singapore).